Future of Meat – Transformation to Plant-based Diet Offers Huge Potential to the Food Sector

The game is on! An estimated 70 per cent of the world’s population plans to consume less meat or quit eating it altogether. Big change offers huge potential for the food sector. Journalist Annukka Oksanen explores the transforming meat industry.

Annukka Oksanen, 28.10.2019

|Long Forms

Ten or fifteen meatballs? Until 2015, hungry furniture shoppers at Ikea restaurants faced an easy decision.

Four years ago, veggie balls and chicken balls were added alongside meatballs, accompanied by salmon and cod balls in 2018.

Ikea has a total of 420 restaurants in 52 countries around the world, which attract an annual 680 million customers. In 2018, IKEA Foods in charge of the restaurants had a turnover of EUR 2.15 billion, making up five per cent of Ikea’s total turnover. Their selection of ‘balls’ are so popular that IKEA Foods has gained a clear understanding of global food trends. It added the veggie balls to the selection simply to cater for the growing demand for plant-based options among customers.

“We know that more and more people choose food based on how ethical, environmental or socially responsible that food product is”, explains Michael La Cour, Managing Director at IKEA Food Services. The choice of dishes is also increasingly influenced by the way food impacts personal health and wellbeing.

Few dishes are wrapped up in as much coziness, love, and safety as the meatball. For Nordic people, meatballs and mashed potatoes are a timeless home cooking classic bordering on a national dish.

Disruption may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about a meatball, but it’s simmering and steaming right there alongside mashed potatoes, gravy, and lingonberry jam on Ikea’s self-service line: meat industry in disruption.

In business terms, the meatball is in the middle of transformation. What’s the difference between transformation and change?

If you think about a board game, transformation changes the entire board instead of the position of players in relation to each other”, says Pekka Mattila, Group Managing Director at Aalto EE and Professor of Practice at Aalto University School of Business.

From the viewpoint of a company, the successfulness of transformation depends on how and when the company reacts to a changing situation. A well-managed, conscious change in a new type of business context is the easiest route.

Researchers Stelios Kavadias, Kostas Ladas and Christoph Loch see a business model linking a new technology to an emerging market need contributing to successful transformation. New technologies come and go, and they do not achieve transformation on their own.

In the trio’s widespread article titled The Transformative Business Model, the researchers from the University of Cambridge Business School analyzed 40 new business models and their transformative potential.

They concluded that a higher chance of success at transformation required better tailored products, asset sharing, usage-based pricing, a more collaborative ecosystem, and an agile and adaptive organization. Also a closed-loop process is important for environmental and cost factors. It means materials that are used and arise in the production process are recycled back into the process as effectively as possible.

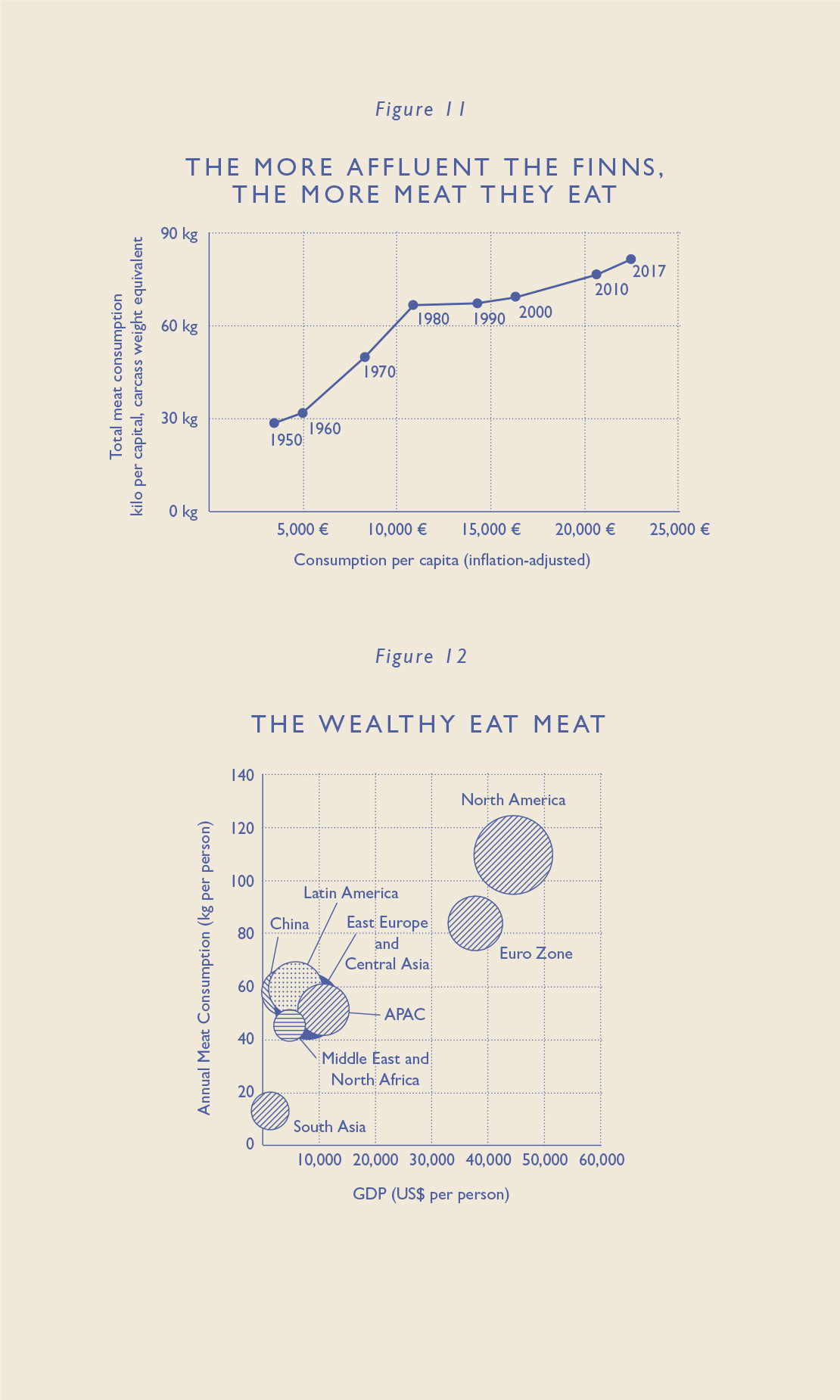

The managing director of IKEA Food Services quotes a report (Global Data 2018) according to which 70 per cent of the world’s population plans to reduce meat consumption or stop eating it altogether.

Despite popular belief, it’s not just a phenomenon in the wealthy west. The figure sounds astounding.

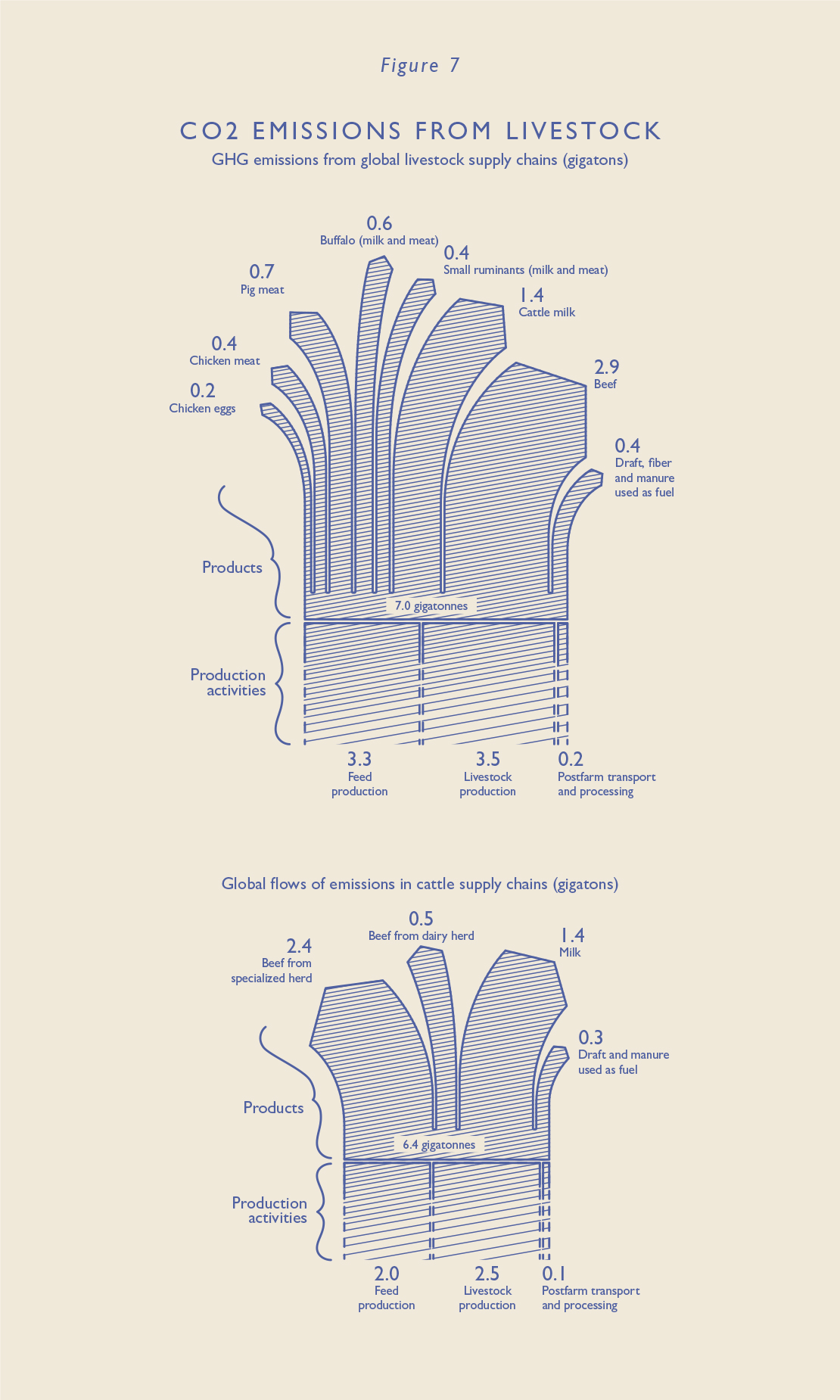

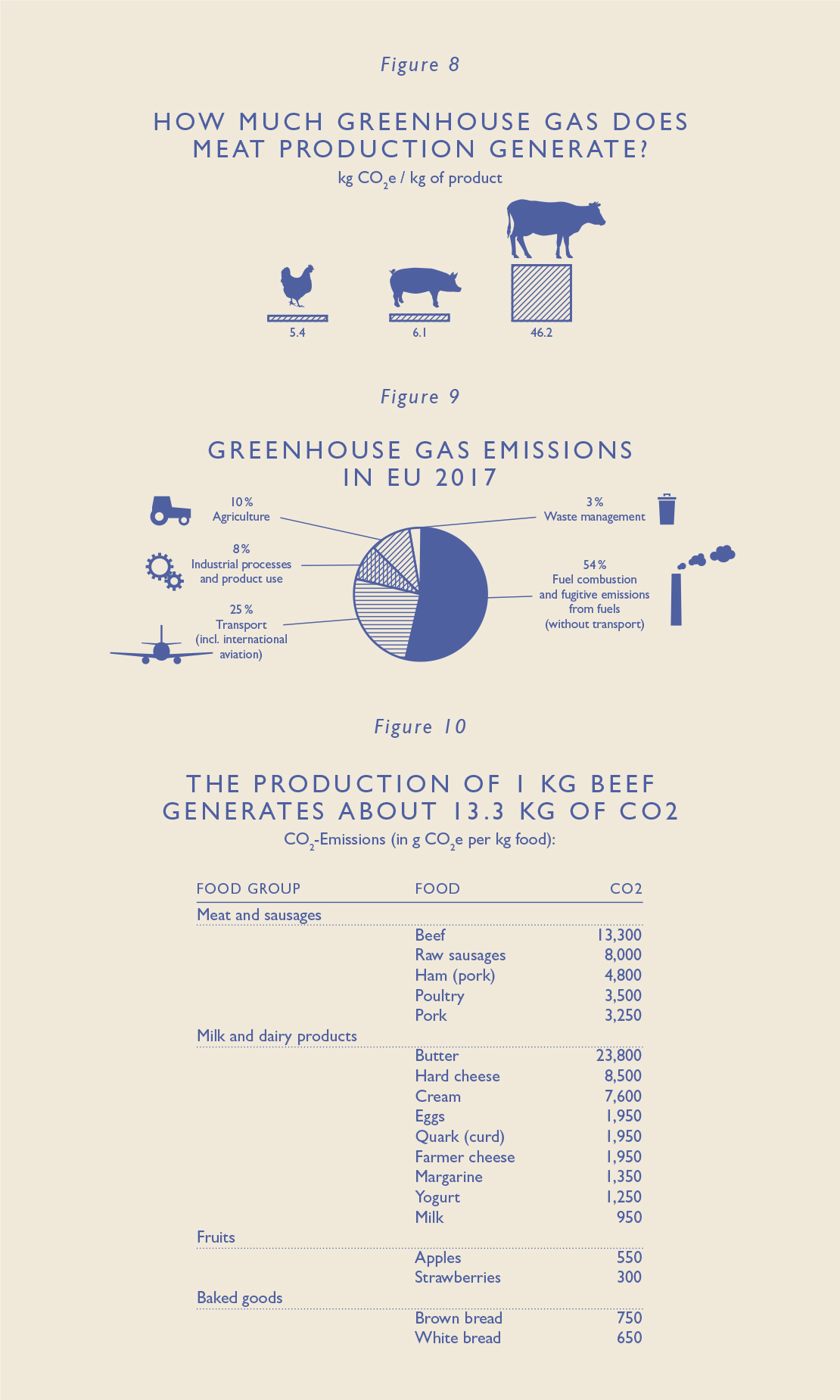

Consumers’ taste buds are changing so rapidly that there’s a demand for new types of products, but even bigger pressure for the transformation comes from production. It all boils down to the climate crisis. At its current scale, meat production is destroying the planet.

According to a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC in 2018, long-term measures to reduce emissions must be carried out rapidly throughout society. It’s the only way to curb global warming to a tolerable level. If global warming continues at its current rate, an increase of 1.5 °C will already be a reality in thirty years’ time. Going over the threshold would pose significant risk to both humans and nature. So far, the IPCC report is the most comprehensive scientific report on climate change that exists.

Without a tolerable climate, there’s no business."

The climate crisis is acute. The impact on business has meant an increasing number of companies putting in every effort to reduce emissions or alter production to be completely emission-free. Now clear-cut climate practices are seen as a competitive advantage and the way to survive on the whole.

Without a tolerable climate, there’s no business.

Of course, also Ikea restaurants have begun to calculate their carbon footprint. “The carbon footprint of veggie balls is about twenty times smaller than that of meatballs”, says La Cour. Companies are busy doing their calculations. It’s also a marketing gimmick. Save the planet, buy veggie balls!

Food is different from other consumption because everyone needs to eat, every single day, where as it is easy to cut down on other types of consumption. The food business cannot disappear – but it’s changing.

Professor of Sustainability Management at Aalto University Minna Halme says people are facing wicked problems, a term commonly used to mean interconnected problem clusters.

There are no simple solutions or labs for testing them. A loss of biodiversity is another problem alongside the climate crisis.

Droughts resulting in crop failure are an example of a wicked problem linked to the climate crisis, causing local wars, which lead to migration, which then contribute to the rise of populist movements. Huh. The entire planet stuffed inside a meatball.

“These factors already have a strong impact on people’s lives. We don’t necessarily notice it here in the Nordic countries, but you don’t have to go far before it’s apparent. Finns live in an illusion if they don’t familiarize themselves with the global situation.”

The required measures for combating the climate crisis are a cause for heated arguments, but the conclusion is always the same: something needs to be done. Despite chain reactions crisscrossing the planet, the situation is not hopeless. Solutions do, however, require fast, painful action.

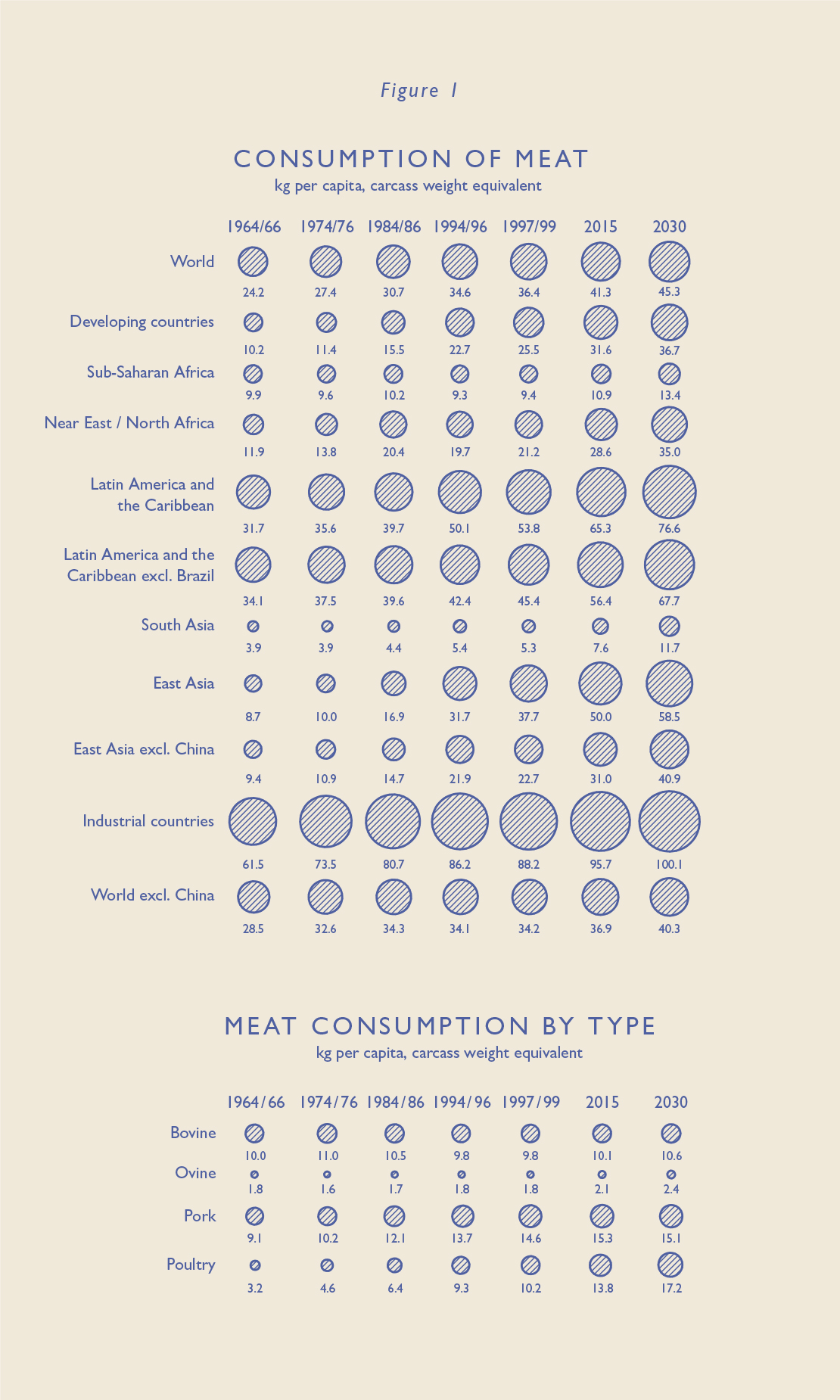

According to a study, an average person on the planet needs to eat 75 per cent less beef, 90 per cent less pork and half the number of eggs. These should be replaced by tripling the current consumption of beans and quadrupling the consumption of nuts and seeds. These actions would halve the emissions from livestock.

According to another estimate, replacing half of the meat products consumed today with lab-produced meat, plant-based meat replacements and insects would reduce the need for agricultural land by 38 per cent. Land is a scarce resource, as pressures mount to use available forestland. Forests store carbon dioxide and shouldn’t be cleared for other use.

Lab-grown meat would be effective, as it means only growing edible muscle, eliminating all livestock waste.

The board game of the meat industry has reshuffled.

The groundbreaking transformation offers huge potential for the food industry.

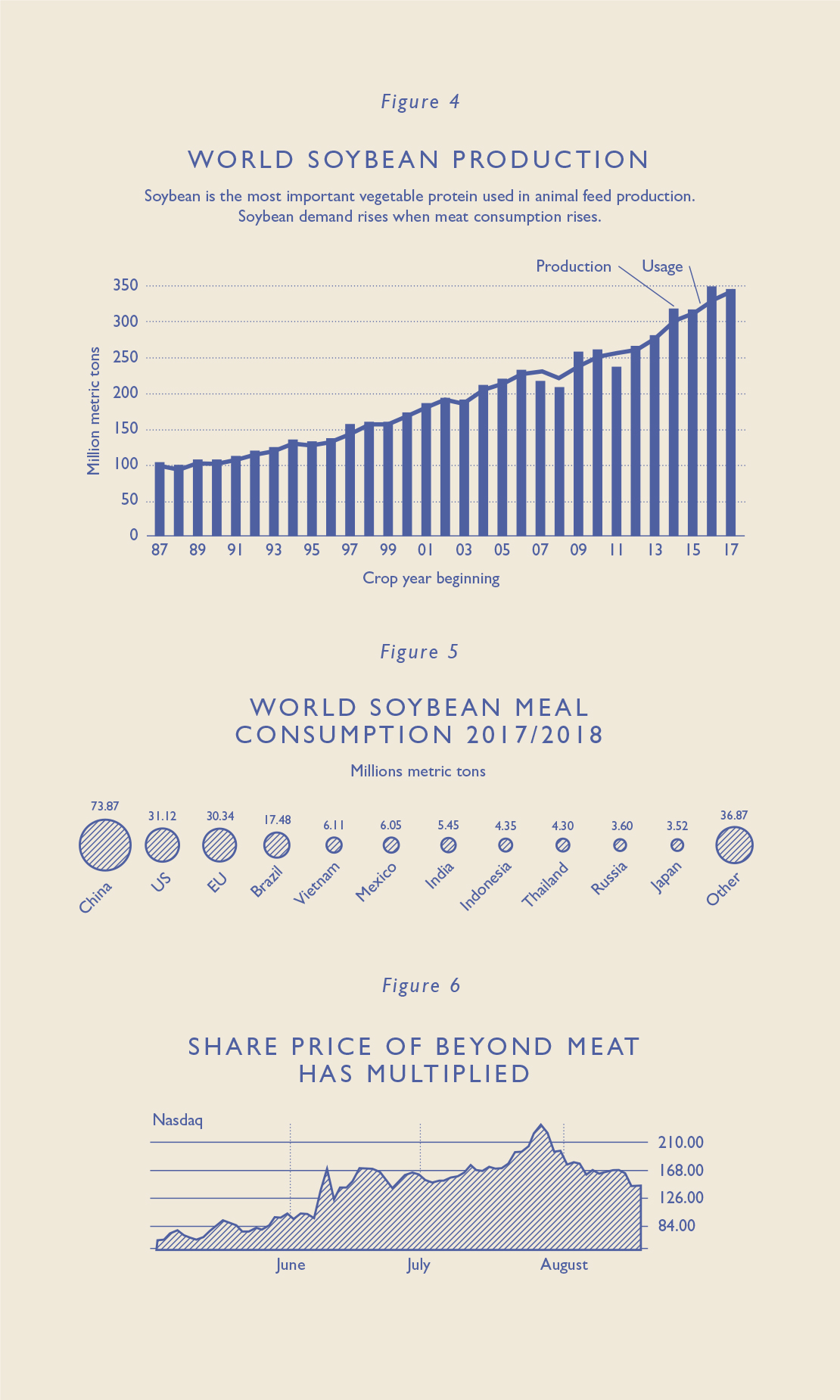

Investors have taken note, and there’s been as much buzz around funding food-related inventions as around Ikea’s meatball counter. Kitchens, fields, and labs are bubbling away, just like the technology industry in the late 1900s. Smelling the aroma of future profits, investors have rushed to the dinner table.

When producer of protein meat substitute Beyond Meat joined Nasdaq in the beginning of May 2019, investors rushed to grab shares. With losses on a revenue of just under USD 90 million in 2018, the company’s market valuation was already close to 5 billion dollars a few weeks after going public. Expectations for future profits are sky high.

The transformation in food production has become an asset management trend."

The stocks continued to rise when investment bank Barclays projected that the market for “alternative meat” could reach USD 140 billion over the next decade, gaining a 10 per cent share of the world’s entire meat market. The forecast was backed up for instance by the plant-based dairy market having a 13 per cent share of the world’s dairy market. This is how the trend can be seen at a café: Coffee with oat milk please!

According to the report by Barclays, animal-based protein will become increasingly controversial, as it is one of the most important sources of greenhouse gas emissions, energy intensive and associated with health concerns.

The transformation in food production has become an asset management trend, and now several investment banks are coming up with their analyses. Themes include solving the methane issue in rearing livestock, growing demand for meat protein and plant protein production.

The popularity is also evident in business and financial data provider Bloomberg offering a chance to follow the Vegan Climate Index since June 2018. The passive index of large cap stocks only accepts companies screened according to vegan and climate-conscious principles. The index has fared better than the S&P 500, the common index used to track the performance of the stock market. A vegan ETF (Exchange Traded Fund) is on its way.

Also meat production itself is undergoing transformation.

Meat giants are now either developing plant protein products themselves or buying out small alternative protein companies – disruptors. For example, Brazil-based JBS, one of the world’s biggest meat producers, has developed a meat-free burger made from soy, wheat, garlic, onion, and beetroot. The market for plant-based protein is on the rise even in Brazil.

Food and drink company Nestlé and US meat giant Tyson alike are involved in development. Quitting meat has made its way to the heart of food culture also in Denmark, which is one of the world’s biggest consumers of meat: smørrebrød, firm favorite among Danes, can now be topped with meat-free, ham-resembling alternatives. They are manufactured by Tulip, which is part of Danish Crown, the world’s largest exporter of pork.

“Meat consumption is increasing on a global scale, but a major climate discussion is underway in our part of the world. Our angle to the discourse is: less, but premium-quality meat”, says Astrid Gade Nielsen, Vice President, Group Communications at Danish Crown.

Disruption has happened also in the Finnish meat market.

In Finland, the majority of pulled oats inventor Gold & Green Foods was acquired by food and drink company Paulig in 2016. Verso Foods, which invented “härkis” fava bean products, was sold to Norwegian Kavli in spring 2019. Plant-based, protein-rich pulled oats made from oat, fava beans and peas, and “härkis” made from ground fava beans can both be used similarly to ground meat.

Leena Saarinen is the former chairman of the board of Verso Foods, now serving as an advisor and a board member. As she tells the story of Verso Foods, it sounds like straight out of a how-to manual for startups. Her background as a company director and professional board member makes her a solid pro in the Finnish food industry.

She believes the business model defined early on was a crucial element for success. According to the business model, commercialization was kept in the company’s own hands, while production was outsourced.

Startups have the advantage of being agile without a heavy balance sheet of machinery and equipment."

“We weren’t tied to a certain production technology. It’s been a clear advantage for us. We’ve managed to put lots of effort into product development despite the company being small. We’ve been able to buy exactly what we’ve needed at the time.”

Startups have the advantage of being agile without a heavy balance sheet of machinery and equipment. And there’s no “this is the way it’s always been done” mentality restricting innovation. Exactly in line with the lessons of transformation by researchers Kavadias, Ladas and Loch.

It all started with an idea of a Finnish protein ingredient. “We first tested peas.”

“At the time, we didn’t have a clue how we’d use fava beans. We didn’t know what we’d make and how it could be used by the food industry. We’ve used different technologies for the chopping, grinding and further processing of beans”, says Saarinen.

Saarinen thinks it worked due to a fast commercialization process and continuously seeking funding alongside product development.

“We discovered fava beans in 2013, and the first consumer products were launched in stores in summer 2014. It happened really fast.”

A product that would resemble ground meat loved by Finns was flickering in the mind already back then, but the first tests didn’t take place until fall 2015. The first actual production tests were carried out in January 2016, and the products were presented to retailers in June 2016.

“That’s the startup spirit. You put your sole focus on a single ingredient, and things begin to happen.” Now Verso Foods is owned by Norwegian Kavli, providing an extra boost for expansion.

“Right now, the professional market is a strong stimulant for growth. Chain restaurants have found us”, Saarinen explains.

The fava bean product is a small but fine example of the transformation in the protein industry: tiny meat alternatives are becoming staples no longer only eaten by vegans.

The products being sold next to ground meat was like hitting jackpot. "

According to Saarinen, retailers are increasingly interested in offering meat alternatives as part of their own brands, which is a strong indicator of changed consumer behavior. It is believed that flexitarians – people who favor a more vegetarian diet with the occasional meat dish – will be causing a boom on the market.

In the Nordic countries, the daily consumer goods sector is highly concentrated. Small producers face giants, and meat alternative manufacturers have to battle with large meat companies for shelf space.

“Distribution channels play a huge role. We managed to get our “härkis” products side-by-side with ground meat, which had a significant impact also on consumer behavior.”

The products being sold next to ground meat was like hitting jackpot.

“Ground meat is the user interface for “härkis”. It’s a new type of ingredient, and consumers need a concept they can compare it to. Everyone knows what to do with ground meat, and recipes for flexitarians are based on ground meat recipes”, says Saarinen.

As far as funding is concerned, parallels can be drawn between the transformation of the meat industry and the technology boom, although production differs due to the meat industry’s heavy infrastructure and slower pace affected by seasons for cultivating animal feed and breeding.

“A pig won’t turn into a chicken at the click of the fingers. Meat production is both slow and fast. Altering the course of production is a time-consuming, expensive operation, and huge losses can ensue in a single day”, says Pekka Mattila from Aalto EE.

The imminent shift is so enormous that it takes support from the EU, states, and stakeholders. The climate crisis affects us all.

”Meat companies need to reposition their products”, says Mattila. Now store shelves are stacked with the same stuff from different brands. Traditional, producer-owned meat companies have strongly centered on production. They don’t always know how to read the market or where the market is heading.”

Meat production is both slow and fast."

There’s not much time, but the situation isn’t impossible. Professor Minna Halme thinks the meat sector still has a chance to react smartly to the looming pressures. “There’s still time to come up with solutions. Now is the time to develop other products alongside meat products. Of course they can choose not to and focus on meat production that’s as sustainable as possible instead”, Minna Halme adds.

Halme doesn’t see the meat industry as an industry of the future if “thinking specifically about meat”. “But if the companies are able to diversify and add to their offering, they come equipped with excellent marketing channels and a lot of muscle force. For them, it’s a totally different ball game than for small, new companies launching a new product on the market”, Halme estimates.

On the other hand, the margins might improve for those traditional companies who manage to renew their production and brands, especially if and when meat becomes more of a luxury product.

A successful change of strategy requires getting serious with product development and building relationships with new producers of raw materials. In the words of Kavadias, Ladas and Loch, the ecosystem needs to be more collaborative.

“These are major investments and elements of a major transformation.”

Self-motivated transformation cannot begin before realizing there’s a need to change. It’s something Mattila thinks hasn’t been fully grasped in Finland with the exception of a couple of small companies. He believes meat companies need to become profoundly consumer-oriented.

“It all goes back to the consumer. Even if your shares in a sausage factory amount to dozens of per cents, you still don’t have much of a say in matters. You can dismiss and hire directors, but it’s consumers who have the power over consumer products”, says Mattila.

The board game has shifted, but so has the position of meat on the plate. Mattila sees the evolution of the meat industry as “where vegetables were previously seen as a side dish, they now compete against meat for the prime spot on the plate”.

“In a context like this, some directors foresee while others react. Hero stories are written about reactive directors who narrowly save a product or company after a crisis. But hero stories should be about directors who foresee; their companies haven’t ended up in crisis in the first place”, Mattila sums up.

Even the dumbest company changes when customers disappear.”

Minna Halme explains that transformation is kindled by pressures from a large interest group and customers voting with their wallets.

“Even the dumbest company changes when customers disappear.”

How long before customers are gone does transformation kickstart into motion depends on the level of awareness among management as well as the level of innovation.

“And whether management is able to take strategic responsibility”, Halme adds.

She has examined transformation in companies for a lengthy period of time. Leading strategy as a forerunner isn’t always easy. When customers or legislation do not yet demand, it’s all down to the director’s strategic capabilities.

“Yet there are those who understand and make a change ahead of others. I can’t think of any meat company in the world that would have done this”, Halme says.

Attitudes towards lab-grown meat is a concrete example of how challenging strategic leadership can be.

One can play it down and say it will take a long time before lab meat can be commercialized. And it sure will; around 5–20 years according to current estimates. One can doubt whether a T-bone steak can ever be produced in a lab, as it would require cultivating more than muscle, such as fat for flavor and to aid cooking. One can also say it’s too expensive if it doesn’t become a mass product. Expensive it is, just like plant-based meat alternatives for the time being.

Then again, things may pan out similarly to the production of renewable energy: sudden giant technological leaps, an increase in volume, a reduction in unit costs. And lo and behold – suddenly energy production concentrated in large plants starts to seem clumsy, old-fashioned, and expensive. In a situation like that, cell-cultured meat becomes the new normal.

There’s no way of knowing which alternative turns out to be the winning strategy.

When an established industry starts to veer towards a new position, technology developers and challengers of the prevailing business model are not taken seriously at first.

They are downplayed. This was the case for renewable energy in the energy sector some time ago.

Next up is denying the change: the newcomer is so insignificant that it doesn’t affect us. Take the Finnish media industry, which long into the 90s believed that the Finnish language would protect it from the impacts of the internet. Also solar and wind power have been downplayed in Finland for a longer time than elsewhere.

When the challenger becomes big enough, it starts to get ridiculed. There have been plenty of vegan jokes flying around.

When the challenger becomes big enough, it starts to get ridiculed."

”Mocking is a sign the newcomer already poses a threat. Finland has gone past the mocking stage in the past few years. Or it might still occur at a men’s hunting club somewhere, but at least I haven’t seen it anymore”, says Halme, referring to the meat industry. Instead of mocking, people may have moved on to thinking about how they should relate and whether to do something themselves.

This is true for the world’s biggest meat exporter Danish Crown. In 2018, it began a process of thoroughly examining the situation in the sector and its position in it. The Danish giant has even discussed whether it should start developing lab-grown meat. For now, the answer has been no.

But Danish Crown has carried out something that is increasingly popular in transformation processes and mentioned as a criterion for success by Kavadias, Ladas and Loch. The company has opened up and taken interest groups actively onboard to grasp the change.

Joint development with interest groups can be called open sourcing. According to professor Halme, it prevents from being misinformed or taking action based on inadequate knowledge. The method not only tolerates differences in opinion, but actively seeks out diverse views. Danish Crown held the MEAT2030 seminar in fall 2018, inviting 200 “inspiring people” to attend. These included people from the entire production chain as well as producers, customers, NGOs, bankers, Ikea personnel, politicians, and a representative from Chinese e-commerce platform Alibaba. The invitees included rivals.

”It was a little scary for some of my Danish Crown colleagues, who had never done anything like it before. We explained it’s good if everyone takes part. Danish Crown had to understand what our stakeholders are thinking – otherwise we cannot run a profitable business”, Astrid Gade Nielsen explains. Gade Nielsen left dairy company Arla, another Danish, globally operating agricultural giant, to join the meat heavyweight. Both companies are farmer-owned. Danish Crown hired her to open up the company, as stakeholders both on the inside and outside needed to hear what is going on in the world.

Gade Nielsen states that during the process of opening up, the company noticed what a big concern the climate was for consumers. Consumers are worried about food production, biodiversity, everything. “Perhaps we need to eat less meat. Less, but extremely good meat. That’s our angle to the discussion”, Gade Nielsen explains, referring to the company’s vision. “We need to think about how we fit in the picture and what we can do about it.”

Where the west is busy talking about veganism, the Chinese pork market is growing at an astounding rate."

For Danish Crown, the solution was to become a sustainable food company from farm to fork.

“The carbon footprint poses a big challenge to the farms. We don’t yet know how we will become carbon neutral by 2050, but we will.”

Carbon neutrality is a key sustainability aim at Danish Crown. The globally operating company has a clear view of the diversity of different markets around the world. Where the west is busy talking about veganism, the Chinese pork market is growing at an astounding rate. Danish Crown runs test production in China and its marketing message there focuses on food safety. It’s a way to start up a discussion on animal welfare and use of antibiotics.

“From there, it’s only a small step to sustainable production. If you want to be a challenger, you need to also challenge customers.”

Customers are challenged also in other parts of the world besides China, as the company arranges courses on sustainable sales for sales people. Danish Crown’s customers include large store and restaurant chains.

According to Minna Halme, consumers choosing a vegetable protein burger instead of beef is a telltale sign that cultural norms are shifting.

The board game is reshaping once again. “Among trendsetters, cutting down on meat consumption has become culturally popular and aspired. It’s talked about a great deal.”

Cultural norms are part of the business ecosystem. The ecosystem also includes legislation, which, too, is showing signs of change. The European Parliament is currently considering whether calling vegetable protein products sausages or burgers is permissible.

Consumption and environmental taxes are on their way.

“For instance, Germany’s federal environment agency proposed raising taxes on meat. Steering behavior through taxation is on the rise”, Halme estimates. Halme and Saarinen from Verso Foods are surprised that a health perspective hasn’t surfaced more strongly in connection to meat consumption.

“The health perspective is interesting when it comes to the excess consumption of processed meat. Eating less red meat has health benefits. In research, the links are more evident than is the case with climate change”, says Halme.

Transformation is a balancing act.

There’s no way of knowing the right time to start. The cashflow needs to continue in motion, and existing production is coupled with developing something new – which creates transformation.

It is not likely that transformation will proceed in a logical and straightforward manner in the meat industry. It almost never does. It can be fast or slow, leap sideways, and turn around. That’s what transformations are like. The crucial matter is to always take care of profitability.

Transformation can create internal tension and processes that are extremely tricky to manage."

Minna Halme mentions Finnish corporation Wärtsilä as an example of successful change management. The company manufactures diesel engines but has a clear focus on the future of renewable energy in its investments and lobbying. Founded in 1834, Wärtsilä can easily be called a top expert in change management; it has seen plenty of fluctuations, lines of business and acquisitions during its 200-year journey.

Transformation can create internal tension and processes that are extremely tricky to manage.

“But failing to recognize upcoming change is what really makes things difficult. Defending the old inevitably leads to it all crashing down.”

“It starts with finding a new identity”, says Halme. She sets the chain of thoughts on the future of the meat industry into motion like this: You can begin to search for a new identity by thinking about the problem the company wants to solve and asking how it can create sustainable, eco-efficient innovation.

“That’s when you begin to find answers to why the company exists on this planet. What do customers need? Protein.”

A meat processing plant can be a provider of protein solutions rather than a meat company.

Where is the transformation in the meat industry heading?

What view should one take when some consumers are only just getting into the habit of eating meat, while a large bunch decides to quit meat for good? How many are flexitarians, and how many players are competing for a share of the same dinner plate? What will we eat in the future?

Transformation always comes with more questions than sure answers.

The shift in the meat sector is the only thing that’s sure. Even Ikea is busy coming up with a ball for the next generation. In 2020, diners at the furniture store will get to taste the fifth version in line:

“It looks and tastes like meat, but is made from plant-based, alternative proteins”, says Michael La Cour, Managing Director of IKEA Food Services.

So in a course of five years, the selection of balls is growing from one to five. In transformation lingo, i.e. the words of Kavadias, Ladas and Loch: “consumers are offered more personalized products”. It’s pretty certain that Ikea won’t be stopping there and has probably begun to investigate lab-grown meat as we speak. A fig tree, recycled plastic storage boxes, a couple of candleholders, a new sofa cover, and two portions of techno meatballs please!

Enjoyed this long form? If yes, you can find more long forms here. You can also order Aalto Leaders' Insight Highlights newsletter to your email to enjoy the fresh stories as well as invitations to free webinars. Order below.

Enjoyed this long form? If yes, you can find more long forms here. You can also order Aalto Leaders' Insight Highlights newsletter to your email to enjoy the fresh stories as well as invitations to free webinars. Order below.