Negative interest rates, long-lost inflation and massive debt recovery have dominated economic policy debates for ages. Now economists predict that brisk economic growth will start in Europe in the summer of 2021.

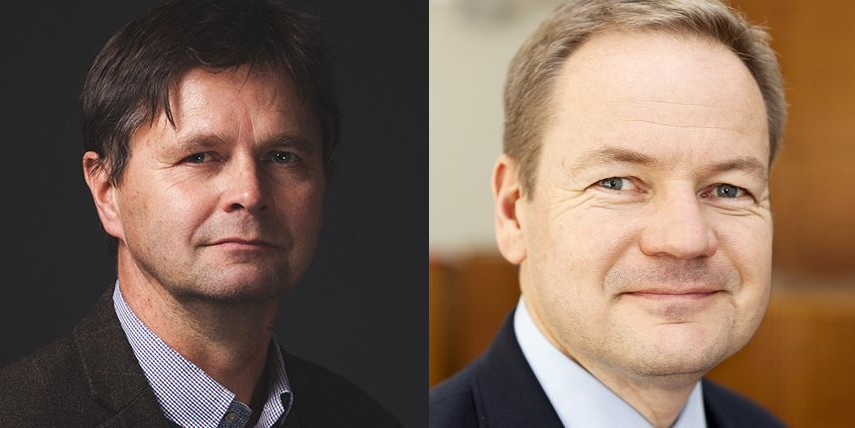

While the current situation is far from ideal, the world economy keeps turning, and things could be much worse, estimate Vesa Puttonen, Professor of Finance at Aalto University, and Jari Melgin, Professor of Practice in Accounting at Aalto University.

Puttonen and Melgin point out that central banks have one principal task: keeping inflation alive but in check. The target level is just under 2%.

“Inflation is the oil in the wheels of the economy. Rising prices create an illusion of growth, which makes managing companies easier,” Melgin describes.

During the financial crisis, central banks had no choice but to concentrate all their efforts into putting out fires. The coronavirus crisis forced them right back into a similar situation. Crisis control demanded overnight decision making.

The economy is still up and running, but inflation vanished. In the European Union, inflation has been below expectations and targets for years. In March 2021, euro area inflation finally rose to 1.3%.

“Ever since 2013, the ECB’s own economists have predicted that inflation in the euro area will rise by more than 1%, close to 2%. As of spring 2021, these forecasts have not been correct once. An increase in interest rates has also been predicted recurrently, but to no avail,” Puttonen notes.

“Some might call the current situation a defensive victory. Without the ECB’s massive action, things would probably be much worse,” Puttonen adds.

Inflation expectations are finally on the rise

In the United States, especially long-term interest rates have now finally started to rise, boosting inflation expectations.

“US inflation expectations are driven by the $1.9 trillion stimulus plan that has already been approved, and the additional $3 trillion stimulus package on the line. Renowned US economist Larry Summers has warned that the stimulus packages are even too big – yet on the other hand, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman sees the risks of short-term overheating as a lesser evil than undersized stimulus plans,” Melgin explains.

“But as Vesa pointed out, economists have been wrong before. It will be exciting to see how the situation develops,” Melgin adds.

Many factors will soon fast-track economic growth in Europe as well. Consumer demand, for example, is likely to skyrocket once the coronavirus situation eases. Simultaneously, the states and central banks will continue extensive stimulus measures.

Do we have any other choice but to try to keep interest rates down – even if that means higher inflation?"

Will this development lead to an overheated economy? Whenever inflation has shown signs of escalating too much, central banks have traditionally fought it by raising interest rates. Puttonen and Melgin emphasize that right now, nobody has the right answers.

“An ideal situation would be about 1.9% inflation and interest rates close to that same level. But I don't see how we could reach this scenario without massive losses. If interest rates rise, it will lead to bond prices dropping and possibly share prices as well. This transformation would be really painful,” Puttonen underlines.

“My prediction is that we will remain at the current interest rate level for quite some time. With debt levels this high, a 2% increase in interest rates would be unbearable. Do we have any other choice but to try to keep interest rates down – even if that means higher inflation?” Puttonen ponders.

For companies with substantial assets, negative or zero interest rates are no cause for celebration.

“Negative interest rates cost companies money. Thus far, consumers have not had to pay interest for keeping money in the bank in Finland, but companies have had to do so for several years,” says Melgin.

“Low interest rates also prevent creative destruction, because the price of money does not weed out weaker companies. Companies that are doing well don’t reap as many benefits from the economic situation as they could, because they have zombie-companies hanging around as their competitors,” Puttonen explains.

Debt cuts would create moral hazard

Puttonen and Melgin emphasize that debt recovery has led to central banks losing significant independence both in Europe and the United States.

“Central banks have never before been such large buyers of government bonds. Central banks now own about half of the debt of Europe and the United States,” Melgin remarks.

The European Central Bank is carrying out huge bond-buying operations to support the economy. In spring 2021, the ECB has purchased bonds on the secondary market for as much as EUR 80 billion per month.

The rise in government debt levels has also given rise to a debate on debt cancellation as a solution to over-indebtedness. What would happen if the ECB were to write off the debts of EU countries?

“Debt that has been accumulated in an exceptional situation, and which has not led to inflation, would not in itself be an insurmountable problem even if it was never repaid. The problem is moral hazard that is created if countries start expecting that they can accumulate debt in the same manner in a normal situation,” Melgin says.

“If we accept that old sins are erased every 10 to 20 years, it will create a wild incentive to commit more sin,” Melgin emphasizes.

“Dead right. If it is done once, what is to prevent us from doing it again. Therefore the first time should be avoided,” Puttonen affirms.

Japan's path is not the end of the world – but it is not a welfare state

Finland's GDP has not grown since the financial crisis. Puttonen and Melgin estimate that Finland's future will look similar to Japan’s situation, unless Finland attracts a great deal of foreign labor in years to come.

“Japan's path is not the end of the world, but it does not offer very inspiring growth prospects,” Puttonen says.

“You should keep in mind, however, that debates about national economy often forget to pay sufficient attention to global aspects. Although Finland's economy has not grown since the financial crisis, the global economy has. International Finnish companies have been doing quite nicely on the world market,” Melgin mentions.

Unless we want to try and attract a lot of foreign labor to Finland, the number of Finns will decrease significantly during the next decades. And this inevitably means that our GDP will fall."

“A real growth rate of 4% and inflation at about 2% is a fairly accurate description of the global economy right now. Companies can make quite a healthy profit in that world,” Melgin adds.

The funding base of the Finnish welfare state, however, will not endure endlessly if the current model persists.

“Unless we want to try and attract a lot of foreign labor to Finland, the number of Finns will decrease significantly during the next decades. And this inevitably means that our GDP will fall,” Puttonen points out.

“Our pension system and our entire welfare promise are based on the assumption that our GDP will grow, and that our population will not decrease. Our system is not agile or dynamic. If the funding base disappears, we have no adjustment mechanisms,” Puttonen concludes.

Vesa Puttonen and Jari Melgin are among the faculty in our Aalto EE programs.